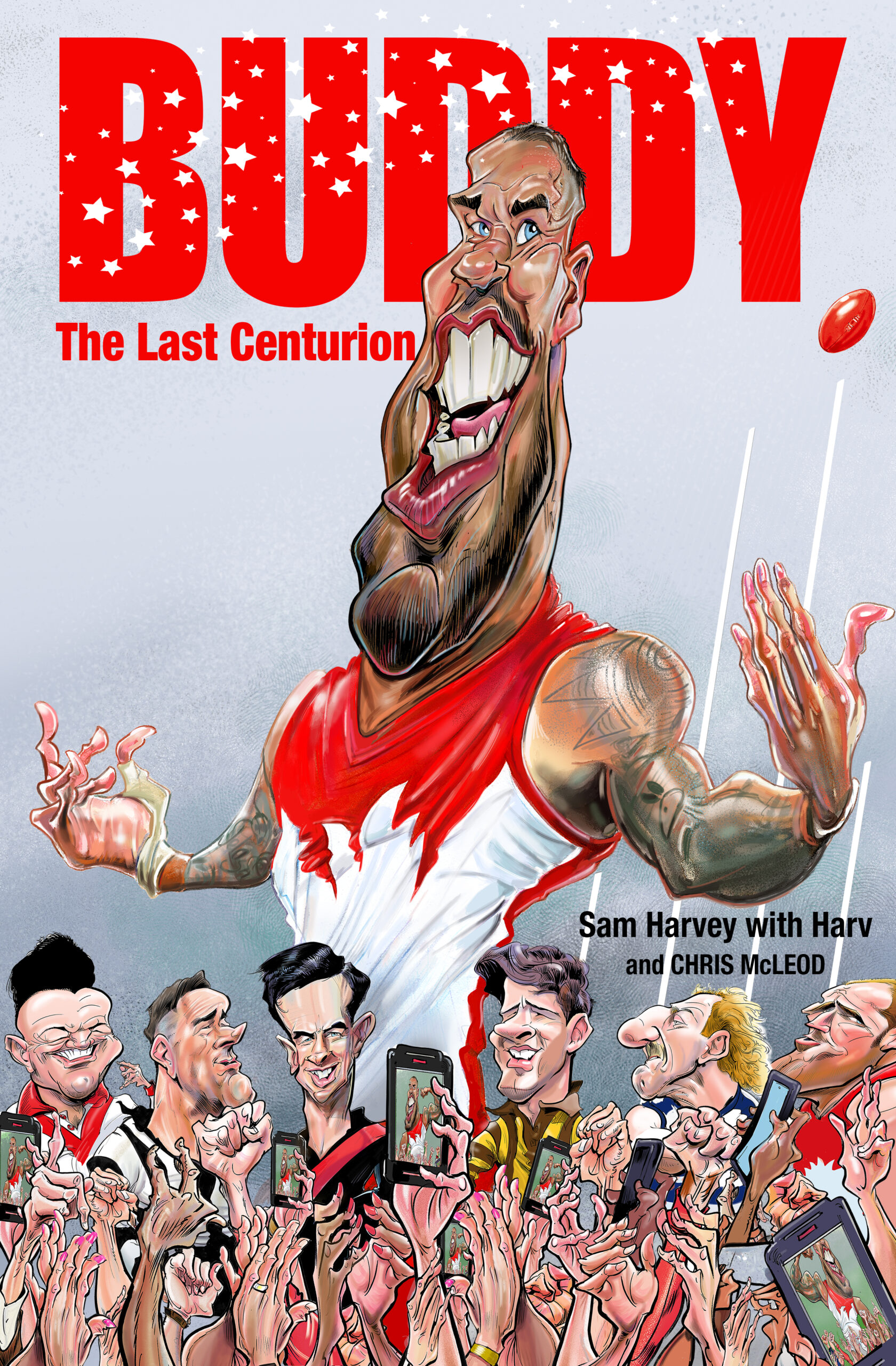

EXTRACT: Buddy - The Last Centurion

THE VITRUVIAN MAN

An excerpt from the first chapter of Buddy: The Last Centurion.

Regarded as one of the most iconic images in Western Civilization, the Vitruvian Man was a pen and ink drawing by the great Leonardo da Vinci around 1490. The artwork depicted the “ideal body proportion”, and it is important because it was one of the first significant sketches depicting art and mathematics working in harmony.

During the Renaissance there were many philosophers who championed Humanism: to emphasize the social and individual potential of human beings. Vitruvian Man is at the centre of the universe. It is regarded as the epitome of human proportion, human perfection.

Lance Franklin is the Australian Rules “Vitruvian Man.” From the moment he ran a 40 second 300m at Dendy Park in Brighton, his first fitness session with Hawthorn, Buddy proved he was something special.

We all remember that famous running goal when Essendon defender Cale Hooker chased him haplessly from the wing. We can recall the 75m goal on a wet day at the MCG in front of 72,000 when he received a handball from Ben Stratton, hurdled Collingwood’s number 41, Sam Dwyer, and hit a long range shot from well inside the square. We knew then this man was elite: we pondered whether the man was built in a test tube; or on Krypton.

Buddy is the perfect physical specimen for an AFL footballer. At 199cm tall, with a wingspan just over 2m, Franklin has the size and build to match some of the greatest sportsmen in history.

Buddy shares similar physical traits to NBA legend Michael Jordan, who is considered as the greatest basketball player ever, human-fish Michael Phelps, and the fastest man on earth Usain Bolt.

Not only is Franklin taller than these men, world sport’s finest, but he has also worked tirelessly on his craft to become “The Vitruvian Man.”

Franklin increased his 2007 draft size of 87kg to 105kg yet has lost none of his pace.

Usain Bolt from Jamaica is the most decorated Olympic sprinter in history, winning eight Olympic Gold medals at three different Games. Bolt defies sprinting physics with his 195cm frame, which is unusually tall for a sprinter. He is notorious for slowly starting his 100m and 200m sprints before overwhelming his opponents and powering home, using his natural long legs.

Buddy’s speed has always been his greatest tool. It is Hawthorn footy folklore that in Franklin’s first pre-season, he ran 20 x 150m sprints at 18 seconds apiece, beating everyone at the club. Usain Bolt’s fastest official 150m was 14.35 seconds.

Undoubtedly the greatest athlete to ever jump in the pool, Michael Phelps is the most decorated Olympian in history, with 18 Gold Medals. With a wingspan of 201cm, a long torso to help him glide through the water and shorter legs that reduced his drag, Michael Phelps was built to swim. Like Franklin, Phelps is the prototype body shape for his chosen sport and has created a long- lasting legacy.

Franklin’s long arms outreach most opponents except the tallest of ruckmen. Buddy then has the wheels to burn away from any ruck tasked with matching him in the air. His long torso makes him hard to tackle. He seems to weave through opposition arms.

As far as freakish athleticism goes, there’s none greater than Michael Jordan. Season after season Jordan used his competitive juices to fuel him to greatness. ‘MJ’ catapulted himself to greatness, and by the end of his career was the most marketable athlete of all time, with a net-worth of $US 1.7 billion.

On physical characteristics alone Franklin matches Jordan’s legendary arm span and clears him for height. As a physical specimen Buddy is hard to beat.

The day Franklin announced himself as the next big superstar of the competition was on 8 September 2007, at the Telstra Dome.

The Hawks had finished 5th on the home-and-away ladder yet were licking their wounds after a 72-point drubbing at the hands of the Sydney Swans who finished 7th. This loss pushed Hawthorn out of the top four, and now they had to face the Adelaide Crows in an Elimination Final. The Crows who were 11th on the Ladder after Round 19, won their next three matches and defeated Collingwood at the same venue in the last round.

This was not going to be easy for the young Hawks side which featured 10 players aged 23 or under. To make matters worse, the Crows jumped out of the blocks early to lead by 19 points at quarter time. Adelaide had pushed out to a game high 31 points lead when their forward Ken McGregor kicked a goal in the 11th minute mark.

The Hawks were desperate for a hero. Enter Lance Franklin. Three goals came off his boot in a five-minute burst and the Hawks only trailed by 2 goals at half-time. Hawthorn kicked a further 2 goals in the third quarter to bring the margin back to 2 points. The Crows rued missed chances, kicking 2 goals 5 behinds in the third quarter. When Buddy kicked his 6th goal in the 13th minute mark of the final term, the Hawks finally hit the lead for the first time.

The anxiousness of a finals victory seemed to have a deleterious effect on the young Hawks as they proceeded to kick 5 consecutive behinds to lose their lead. Closing in on the 29th minute mark and still down by three points, Hawks half-back flanker Ricky Ladson marked a short kick from stalwart Shane Crawford and sized up his options. It was a heart in your mouth moment when Ladson drilled a laser pass to Franklin, who would have the shot to win the game from just outside 50.

With what is now famously known as the “Buddy Arc,” Franklin who’d kicked 2.11 two weeks previously on the same ground, calmly went back, and slotted the memorable sealer. He turned around to the crowd with his arms outstretched. He looked for all the world the model for Da Vinci’s anatomical sketch.

From that moment on, Buddy’s life changed forever, playing a further 181 games for Hawthorn, and 580 goals before joining the Sydney Swans.

The young Hawks, who had not won a final since 2001, went on famously to win the 2008 Premiership, with Franklin becoming the last player to kick 100 goals in a season.

If you took away Franklin’s natural ability and athleticism, he wouldn’t look out of place as a key position forward playing lower- level tough-as-nails suburban footy with his long kick and tattoos.

It is no lie that Buddy has struggled with marking the Sherrin over his head and has used his right foot fewer times than Australia has had Prime Ministers. Still, Franklin encompasses all the distinct traits that enabled the greatest forwards in the game’s history to kick 1,000 career goals. Each of the great forwards has a unique quality that sets them apart. Franklin possesses the athleticism of Ablett Sr, the aura of Lockett, the unselfishness of Dunstall, the durability of Coventry, and the long, booming kick of Wade.

Buddy performed his miracles at much different period in football as well. A period, designed by myriad coaches to curb the influence of the forward as never before in the game.

In the 21st century it has never been full-forward v full-back, one out in the square, as it was in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. The tactical defensive mindset of many modern coaches has made defenders smarter; they intercept in the holes and zone off the space.

It hasn’t been a picnic, yet Buddy has continued to be damaging. His trademark ability to break defensive zones and kick long-range goals from 50m+ continually has been able to counter even the most miserly team defence.

It may take footy lovers some time to digest the magnitude of 1,000 goals in the AFL era.

The Athleticism of Ablett Sr

Unlike the other predominant full forwards on this 1,000 goal list, Gary Ablett’s athleticism saw him able to push up the ground and use his strength and pace to drive the Sherrin forward.

Lance Franklin shares these traits, and although they have kicked 1,000 career goals, these two aren’t your typical stay-at-home full-forwards and only made a move closer to the goalmouth later in their careers. This is evident by the fact that Ablett Sr (12.85) and Franklin (10.70) averaged more kicks a game than Lockett (10.20) averaged disposals. Since stats were officially recorded in

1965, Ablett and Franklin are the only two footballers to average 15 disposals and 3 goals a game for their career.

What separates them from the other full-forwards is that even though they both liked to play up the ground, Ablett hit the scoreboard 1,721 times during his career at an average of 6.94, the same average Lockett had over his 281-game career.

Franklin has hit the scoreboard more than anyone in the modern century with 1,776 scores at 5.21. That is 569 more times than Jack Riewoldt, who has played 20 fewer games, and a higher average than Matthew Lloyd, who hit the scoreboard 1,350 times at an average of 5.00 across his 270-game career. Ablett and Franklin also share the uncanny ability to manoeuvre their body in tight traffic and find the goals. This is why they are regarded as the greatest footballers of their era.