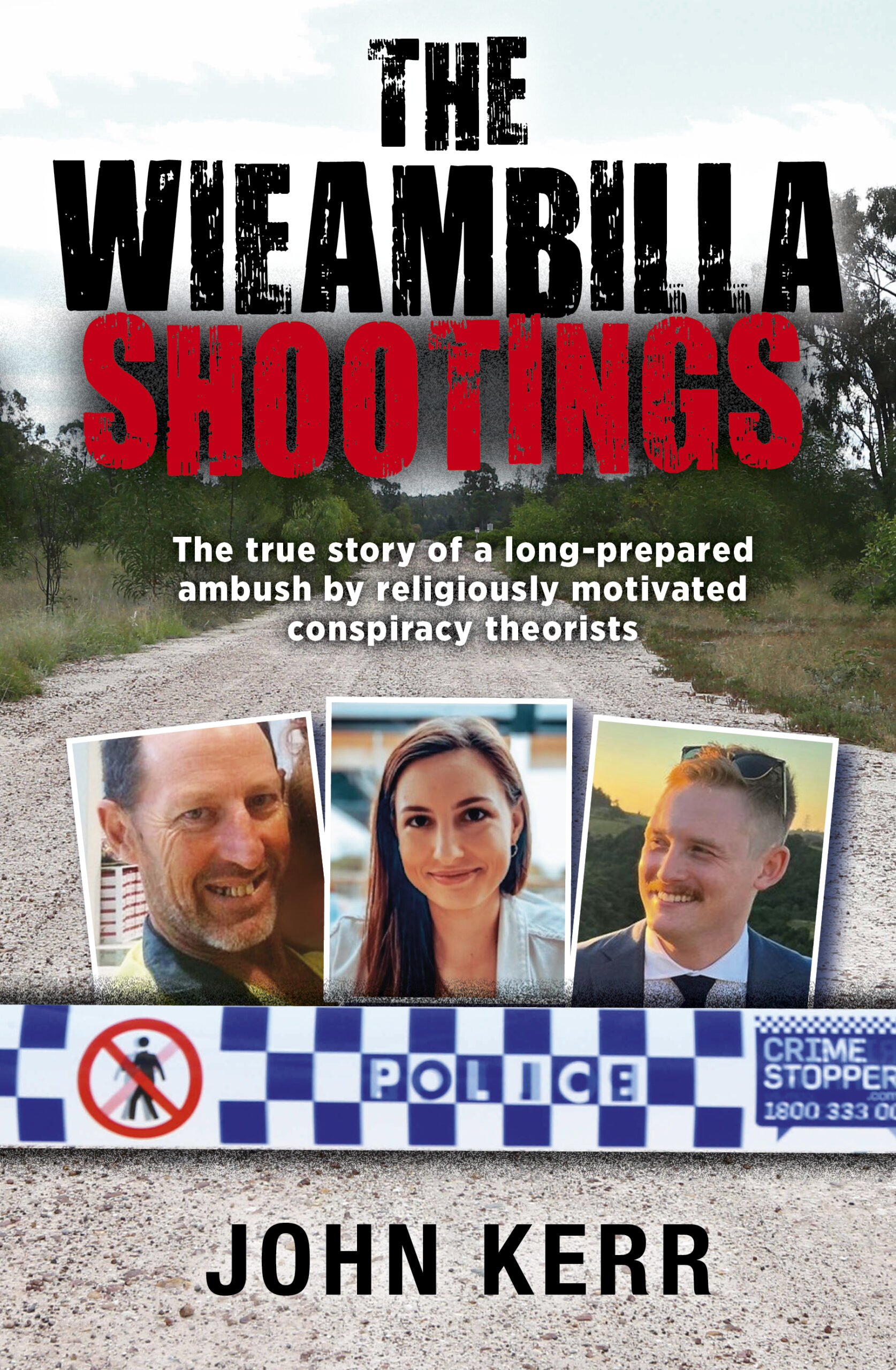

EXTRACT: The Wieambilla Shootings

THE WELFARE CHECK

An excerpt from the first chapter of The Wieambilla Shootings

When police make a welfare check, a routine job for city and country cops alike, what usually happens is that officers knock on doors, or press a buzzer or intercom. In the country, particularly on isolated rural properties, they may sound a car horn or walk about the outbuildings and holler a bit to get the attention of one or more of the residents. If no- one’s home, the usual thing is for an officer to leave his or her card, and write a note asking the key resident to get in touch with whoever is on the police department paperwork.

If someone is home, one officer generally starts with an ‘are you So-and-so?’ or ‘when did you last see?’ type of question. The information gathered is recorded in their notepad or on their phone recorder app. They may ask the resident to show some photo identification. Then the rest of the job is done back at the station, where the file is updated and circulated to police involved.

Four on-duty Queensland Police Service constables in two vehicles drove to an isolated bush block, 251 Wains Road, Wieambilla, Queensland about 4.30 on Monday afternoon 12 December 2022, to make a welfare check. They may too have had an arrest warrant to serve on the missing man too, as we will see.

The estranged second wife of Nathaniel Charles Train in New South Wales had had no contact from him for over two months. He had uncharacteristically gone incommunicado; he was a recovering invalid; his behaviour had become odd; she was worried about him. She contacted local police. They had mechanisms for worries like this. A NSW Police Service missing-person file was created. Queensland Police were copied in because Nathaniel’s brother, Gareth Train, lived on the Wieambilla block, and he may have known something useful regarding his brother’s whereabouts. According to the Queensland Coroner’s Court, NSW Police may also have contacted the Chinchilla Police Station specifically requesting paying 251 Wains Road a visit.

Nearly 30 people a day go missing in NSW alone. Most are quickly found and welfare checks find most of them.

A missing person file request is not the only origin of a welfare check.

This author had an elderly friend living in a small country town who, uncharacteristically, was not responding to phone calls or emails. On my visits from the city to see him, we had laughed about how he had look down to see if he was barefoot or in his socks or was wearing shoes, his peripheral neuropathy having deadened feeling in his feet. Sufferers cannot, for example, climb ladders safely but that does not mean they will not give it a go. And fall off. Worried, I rang the local one-man police station. The officer said he was just going out to walk his dog, so he would call in. I said there was a dog on my friends’ premises. He said, ‘Betsy and my bitch get along OK, no worries.’ Within an hour, the cop had rung back to say all was sweet. In his log, a welfare check.

Garry Disher’s fictional Constable Paul (Hirsch) Hirschhausen of the one-officer Tiverton Station in ‘wheat and wool country’ in remote South Australia is a cop with a big beat. Readers of these well-researched thrillers will be aware of Hirsch’s regular weekly round trips, ‘patrols’ he calls them, calling on the isolated, the vulnerable, those at-risk of re-offending, the frail or mentally ill, dysfunctional families and the odd eccentric day-glo crazy camped out. Regular welfare checks.

What the four cops faced at the Wains Road gate at 251 is not known outside a group of tight-lipped insiders who heard it from the survivors.

Like quite a few others on the Wieambilla blocks, Gareth Train valued privacy. At 251 Wains Road the four passed a ‘No Trespassing’ sign. If the gate was unlocked, that itself may have sinister implications. What we do know is that the homestead was not visible from Wains Road, that trees held security cameras and mirrors in place covering the approach, and that the inhabitants knew the cops were coming.

The two constables from the Tara Police District seem to have led the way, the two from Chinchilla falling in behind. They drove up the long driveway. They pulled up at the gate of the fenced-off homestead-and-sheds area. One of them honked the horn, a practical thing to do, a courtesy.

That four police should attend a welfare check has raised suspicions.

Even a retired Northern Territory and Australian Federal Police cop of my acquaintance queried it in conversation. But such calls are also opportunities to familiarise colleagues new to the area with the roads, point out tricky spots, highlight navigation landmarks, and acquaint them of addresses with ‘history’, places with residents with repeat offences on their record or a reputation for violence or heavy alcohol or methamphetamine use.

These four, none of them old hands, had a rookie just eight weeks on ‘The Job’ among them. Also, while the Wieambilla blocks lie within the Tara Police District, they border the Chinchilla one and districts cooperate. Police services are never lavish with staffing, so if, say, Chinchilla’s officers are tied up and get a call that perhaps Tara can do… and vice versa.

The two Toyota LandCruiser Prado hatchbacks stopped in front of the house area’s fence. The four cops got out.

The homestead gate at 251 was locked. No worries. Tara Constables Matthew Arnold and Rachael McCrow, and Chinchilla Constables Randall Kirk and Keely Bough all climbed over the fence and began to walk up to the silent house. Nobody appeared from within it, as the police’s body cams attest. The four would have been in clear view to anybody in the house or in the hides and foxholes covered with scrub around it.

I cannot be sure, but it seems that no-one was in the house. The three residents – Gareth, Stacey and Nathaniel Train, or at least two of them – were in the long-prepared sniper beds outside, the kill zone long planned, dressed to kill in camouflage gear; they had either had time to dress for the ambush or had dressed like this every day in the general expectation of a visit.

Gunshots rang out. In the hail of bullets fired Matthew and Rachel were felled instantly. They did not have a chance.

When I started this book, I wrote ‘Hopefully, they died instantly.’

I hoped the bullets that first felled them, killed them; that they went from unsuspecting daily-routine consciousness, to shock, momentary confusion, unconsciousness, and a quick death. My hopes may have been the fate of Matthew, who said to have been shot in the midriff, perhaps halfway over the fence, but Rachel was hit in the leg. Randall took a wound in his leg too but was able to walk.

Randall was able to get to the cab of the Chinchilla police car. Bullets smashed through the windows. He kept low, and hit the ignition. Bullets continued to smash into the van, showering him in glass shards. His impending escape seems to have attracted all the shooters’ attention, diverting it from Keely. He was able to drive out of the line of fire and get to a place where he could make contact with station police. It is not clear, but it seems a mobile phone connection may have been necessary. Connection in the area is not good.

Keely Brough was not hit. She too ran from the area in front of the gate, but she found no cover. That may have saved her life. She dived into the long grass and stringy, thin open brigalow and gidgee scrub that grew at the side of the driveway, praying no bullet – and plenty of them were flying – would find her body. She crawled into the dirt, and hid. She rang 000, may have got through. She perhaps radio-ed colleagues. These communication questions remain open. But she kept her body cam running.

Two Train shooters walked up to where Matthew Arnold had fallen.

They took his Glock sidearm and shot him in the head with it, very probably and hopefully, a post-mortem insult on dead man. They took his two-way radio too. Reports of what happened next are confused and unreliable. However, it is my melancholy duty to write that some have reported that Rachel had made or was making a tourniquet to stem blood loss from her leg wound as she pleaded for her life, that she was killed by an execution-style bullet to her head from Matthew’s Glock. If so, the cruelty of the Trains is made more terrible. If so, Rachael died not only in pain, but in terror.